Nathan Gilles is an artist. His medium is wood, his focus Native American carving. He makes bowls, masks, drums, boxes, hand tools — pretty much anything in the genre. He even made a traditional dugout canoe once, which you may have seen. It’s been on display in front of the museum in Coupeville for years.

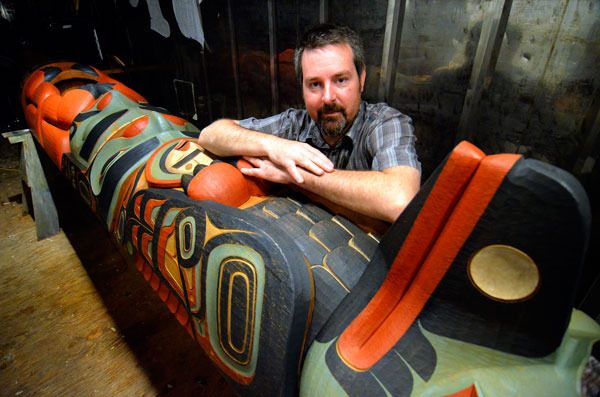

But it’s totem poles that are Gilles’ specialty.

Over the past two decades, he’s worked on nearly 30, either as a solo artist or in a team. He holds an art education degree with a Native American education speciality, is skilled in all seven totem pole styles, and would be considered by most as a “master,” though it’s not a title he prefers. There are only a few dozen carvers in the region, he says, and each has their own approach.

“It’s like a visual language,” said Gilles, in his makeshift workshop off Maxwelton Road. “It’s like a dance.”

Such artists shouldn’t be marginalized with superfluous characterizations of skill, he says. Even with all his experience, it was only in the past few years that Gilles reached a skill level where he can consistently and effectively communicate emotion. It was an important milestone, one that took more than 20 years of study to accomplish.

Most of Gilles’ totem poles were created for the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe, a smaller tribe that’s invested heavily in traditional art. Gilles’ work can be found in the Jamestown Tribal Center, 7 Cedars Casino and at Jamestown Tribal Medical Center.

“I have great respect for him and his talents,” said Jerry Allen, CEO of 7 Cedar Resorts and Properties.

“Nathan’s contribution has been fantastic,” he added.

Gilles spent his early youth in the Midwest but is a South Whidbey High School graduate. He’d always had an interest in Native American culture, but he got hooked after meeting a few artists from the Lummi Nation who visited South End schools.

He attended Western Washington University and received a teaching degree with an emphasis in art. There was no program that focused on his specific area of interest, however, so he spent time on the Lummi reservation and the Northwest Indian College gleaning whatever he could.

“I had to go around and ask all the old guys questions,” he said.

Gilles would later spend years as a high school art teacher on the reservation, and polishing his skills working for master carvers such as Jamestown’s Dale Faulstich in the House of Mythes, and others around Puget Sound.

His long efforts have paid off. He’s developed a name in the business, both in a professional and literal sense; he is Too-sem’-tian, an ancestral Samish name that embodies a lineage of past tribal carvers. It’s a moniker he will retain until his death.

His work also appears to be in some demand, particularly with the Jamestown S’Klallam. They scooped up his most recent piece, a traditional entrance pole with a hole near the bottom, almost immediately.

“Within 24 hours after getting it done I got it sold, so I’m pretty excited it didn’t sit around as yard-art,” he joked.

Totem pole prices can vary, but professionals typically charge between $3,000 and $5,000 per linear foot, Gilles said. This one is 12.5 feet long.

Gilles plans to use some of the money from the sale to build a longhouse-style studio at his home in Maxwelton. He returned to South Whidbey a few years ago to help his father, Greg Gilles, start Seven Generations Artisan Meats, a home-based butchery. The business was put on temporary hold — the men were sidetracked with other projects — and Nathan Gilles has used the refrigerated cooler as a make-do workshop.

The new studio will be a place where he can work, sell his art and teach. Passing on what he’s learned is something he’s looking forward to. He’s a teacher at heart, and the art form is rare, having seen a resurgence only in the past 50 or so years.

“There are probably as many artists working now as there were in historic times,” he said. “But there’s still none that have reached the masterfulness of 200 years ago. There’s still so much to learn.”

His hope is to begin construction this summer and be open for business before the end of the year, though he may begin teaching classes immediately if he can find a temporary and suitable location.

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated Nathan Gilles’ education. He has an art education degree and a Washington State teaching endorsement with a Native American eduction specialty.