When local historian, linguist and author Michael Seraphinoff saw the bundle of 200 letters of a Civil War soldier that his wife had received, he practically began salivating.

“It was like she was waving a beehive full of honey in front of a hungry bear,” Seraphinoff said.

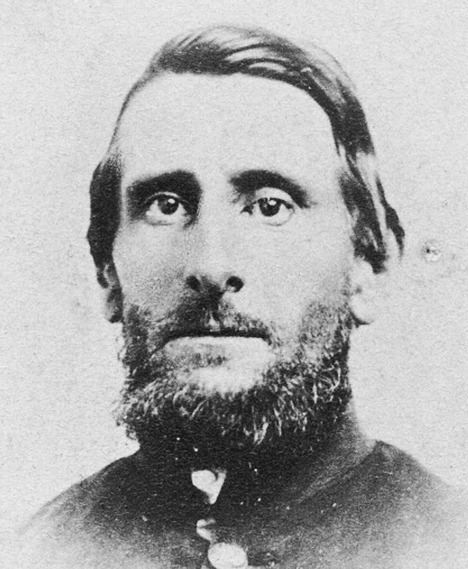

His wife, Susan Collingwood Prescott, had received copies of the letters of Lt. Joseph W. Collingwood, her great-great-grandfather. Collingwood had written the letters to his wife Rebecca during the 18 months he served in the Union Army of the Potomac during the American Civil War, in the months between August 1861 and December 1862.

The letters had come from an archive in the Huntington Library in California, which houses a collection of rare American and British books and manuscripts.

Prescott and Seraphinoff dove into the letters, and the Greenbank couple were transported back in time. They spent winter evenings sitting in front of a woodstove reading the letters aloud to each other.

Seraphinoff realized that such a personal documentation of life during an important time in American history might interest a larger audience. In order to share some of the messages he found from reading the letters, Seraphinoff will present “A Soldier’s Letters Home” at 7 p.m. Thursday, May 20 at the Freeland Library.

“The letters proved a revelation in a number of ways for us,” Seraphinoff said.

“Joseph Collingwood was quite expressive and provided considerably detailed descriptions at times of both his daily life and of special events, incidents and moments in army life.”

After marrying Rebecca W. Richardson and settling in Plymouth, Mass., Collingwood, a fish market owner, eventually found himself in financial straits. He turned to the military.

He enlisted in the volunteer militia and later became an officer in the Army of the Potomac, four months after the start of the Civil War.

“The letters were instantly engaging,” Seraphinoff said.

“First of all, there was the sense of immediacy of their message that we hadn’t expected, although it was nearly 150 years since they were written.”

In the letters home, Collingwood describes people, complains about or praises individual soldiers or his fellow officers, and even gives a political opinion at times, Seraphinoff said.

“He even gives fairly detailed descriptions of troop strength, morale and even location, all things that the modern military censor would have made sure were not part of any correspondence home.”

Still, the letters were also highly personal.

“He seems to have wanted to improve his financial situation,” Prescott added.

Indeed, one letter refers to Collingwood’s previous bankruptcy, and by reading some of the letters, it is obvious that being able to send money home to his family was a great source of satisfaction for the soldier, and the reason why he enlisted in the first place.

In a letter dated Sept. 2, 1861 he describes the regiment’s arrival in Washington, DC and their march before President Lincoln and the commanding general. “Abe … looks overworked,” Collingwood noted.

Both Seraphinoff and Prescott recalled the extraordinary respect that Collingwood showed toward his wife in the letters, especially considering the period in which they are written. In his treatment of her as his equal, the letters become extraordinarily informative, they said, because he tells her everything that is on his mind, no matter how gruesome, bitter or personal.

He occasionally reminds her of his role in the great national struggle but, as the war rages on, he shares the terrible carnage and waste of the war after the battles at Manassas Junction and the second Battle of Bull Run.

A week after the Battle of Antietam, considered the bloodiest one-day battle in U.S. military history, on Sept. 24, 1862, he writes: “It is an awful sight to go over the field after the excitement is over. Especially such a battle as last Wednesday. In some places the dead lay on top of one another while the wounded lay in all directions. Some crying for water. Some for a surgeon. Some praying. Some cursing. But the most of them quietly waiting their turn. Many of them are thinking of the loved ones far away that they are destined to see no more.”

Reading on in the pile of letters, Seraphinoff said Collingwood becomes more bitter with each day at war.

On Dec. 7, he mentions that the Union Army is too late in arriving at Fredericksburg, and that an assault on the heavily fortified site would now be a mistake.

Later that month, Rebecca receives a letter informing her of her husband’s death after being wounded at the Battle of Fredericksburg.

Both of Collingwood’s brothers would be killed in the war, as well. By the end of the conflict in 1865, the war had claimed more than 620,000 soldiers, Union and Confederate.

Seraphinoff said that not only are these letters a unique insight into the minute details of a soldier’s perspective in the thick of the Civil War, but that Collingwood also gives clues about the complex culture of the time, which he will expand upon during the presentation.

Ultimately, with Memorial Day approaching and thoughts turning to all the veterans of all the wars who have served this country, the historian in Seraphinoff compels him to want to share Collingwood’s letters with as many people as possible. Such an eloquent articulation of the effects of war on a person, a family and the wider world, is a powerful testament to the cost of war, Seraphinoff said, which always ends up to be more than anyone can appreciate.