Looking for a challenge and adventure, Brian Johnston left the quiet shores of Whidbey Island to work in Baghdad earlier this year. OK, that’s an understatement.

Johnston, a contract manager for a private corporation, had been working on projects at Whidbey Island Naval Air Station until this fall. But the former Freeland resident wanted to try his hand at overseas construction.

“I have always wanted to experience the challenge and the adventure of working overseas,” he said from his temporary quarters in one of Saddam Hussein’s former palaces. “Every day there is something new here.”

Johnston is working on a military installation near Baghdad. His company, which would not allow Johnston to be interviewed if named, is building water and electric infrastructure on three U.S. military bases. The U.S. government has awarded billions of dollars in construction contracts in Iraq. One of those contracts went to Johnston’s company. The biggest U.S. government contractor in Iraq is a subsidiary of Halliburton, the oil services company once run by Vice President Dick Cheney. Johnston does not work for Halliburton.

“I’ve always wanted to do construction management out of the country. Something totally different and there are new weird challenges everyday.”

For example, how often does a person who is not in the armed forces have to coordinate with the Army a ride to work? Ride in a tank, anyone? Or, how often does an American get a chance to live in one of Saddam Hussein’s palaces? He does.

Johnston lives on one of the military bases where his company is working. His neighbors are 1,400 other Americans, all contractors and military personnel. Though they are technically in hostile territory, they’re equipped to be safe.

“About 1,200 of them carry guns,” Johnston said in a recent e-mail “Even the civilian population is a deterrent.”

Although family and friends are concerned for his safety, Johnston said he feels secure most of the time. Having served in the Vietnam War, he is familiar with the sounds of combat.

“When car bombs explode in Baghdad, the windows rattle here,” he said.

“During a recent telephone interview, Johnston reported seeing white flares of small arms fire just outside the fence to his compound.

“At times I hear AK-47 fire with scattered mortar round explosions,” he said.

Fortunately, these sounds are not constant. Several days later, this was Johnston’s e-mail from Iraq.

“It’s pretty quiet for the last two nights, and that is also a relief, and keeps everyone less edgy.”

Recently, two South Korean contractors were killed in Iraq. Another 60 South Korean contract engineers and technicians working for the U.S. government on a project to fix power lines north of Baghdad decided to leave the country after the incident.

To cut the risk of more deaths among civilian contractors, Johnston’s movements are restricted to the three camps in which he works. That’s fine with him, since there is so much work to do.

“A lot is tying figure out what exists… then how to make it usable for the military for the next two to three years they are expected to be here,” Johnston said.

His company is planning is construction projects for a longer haul than originally envisioned when the United States invaded Iraq in 2002. At the time, President George W. Bush stated that the U.S. military was likely to stay for just a year.

Iraq is a completely different world than what he is used to. Arranging for military escorts and trying to communicate in Arabic and several other languages are just some of the everyday tasks Johnston faces. His crew consists of about 200 people — three-quarters of whom can’t speak or understand English — who are bused in every morning. Johnton’s subcontractor is Egyptian and work crews are Iraqi, Armenian, Kurdish and Turkish. It can get confusing, Johnston said.

“Here there are three categories of humans… local nationals, third-country nationals and American expatriots or expats.”

Communicating with those various categories can be a challenge.

“I’m trying to learn Arabic, so all the folks are putting out words to me, and I tell all that if everyone works with me, by the end of six months, I will have the vocabulary of a six year old,” Johnston wrote in an e-mail.

Johnston said he knows about 100 Arabic words now.

One of the things that keep the days sane is the regular beat of life. Most mornings begin with a sunrise run for Johnston. He then Johnston meets 10 to 16 buses full of workers at the gate every morning. His first job of the day is to search every worker before they come into the compound.

“I have them open their coats and with the men I pat them down looking for weapons,” he said.

A female employee searches the women workers, most of whom are domestic workers.

In spite of these security matters Johnston says he really enjoys the people he works with.

“I really like the Iraqi people they are happy and funny and very hard working.

Johnston said the Iraqis he works with are supportive of the U.S.

“I hear a lot of positive feedback about America and the military. They use hand gestures, the ‘knife across the throat’ and they say, ‘Sadaam bad, America good.’”

Johnston said he believes they are sincere, at least for the moment.

On the other hand, the Arabic media is not so positive about the U.S. Johnston said Arabic television and radio include threats of reprisals against Iraqi’s working for the U.S. and U.S. companies. But that does not color his thinking about the people of Iraq. Johnston knows they live hard lives.

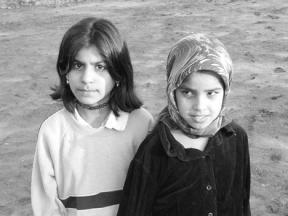

“It’s hard not to adopt them and try and take care of them,” he said in an e-mail. “We see many Iraqis living in poverty… right outside our gates. Abandoned buildings have become homes for families. Some children stand outside our fence and beg.”

Johnston said it’s difficult not to help everyone.

As the holiday season approaches, Johnston said the Americans will try to bring some cheer with a Christmas party. Johnston’s party guests will include Christian Armenians, Turks Kurds, as well as other American contractors and military personnel.

“We’ll pretend like we are home for awhile,” he said.