There’s something about Langley that draws accomplished artists to its shores.

Even in the rugged days of the early 1900s when the area was mainly a frontier for farming families, Langley managed to attract its share of artists and actually became home to a forward-thinking artists colony.

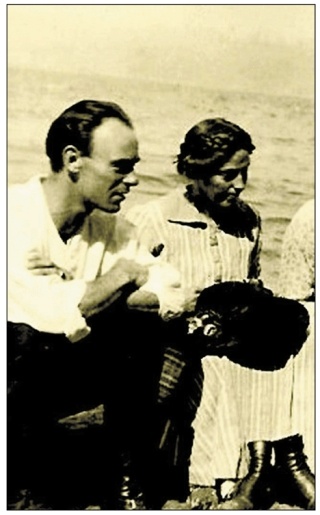

Margaret and Peter Camfferman were progressive painters who moved to Whidbey Island in 1915, where they established the Camfferman Art Colony at their home, Brachenwood, off Saratoga Road in Langley.

The Langley Historic Preservation Commission, along with the South Whidbey Historical Society and Sno-Isle Libraries, has planned an evening to tell the story of these two exceptional artists. The program is part of the National Historic Preservation Month celebration, and is planned for 7 p.m. Thursday, May 21 in the North Star building adjacent to Langley City Hall.

There is a lot more to the story of the Cammfermans than meets the eye.

The interest in these painters all started when Langley librarian Sheila McCue recently discovered that one of Margaret Gove Camfferman’s still lifes had re-surfaced after having been stored in the recesses of city hall.

McCue was inspired by the painting and began a determined search to find out more about the artist.

McCue realized that Margaret Gove Camfferman was the niece of Helen Coe, the first mayor of Langley in 1919, who was instrumental in building the Langley Library. The library currently has four other Camfferman paintings on display.

McCue’s search also led her to David Martin of Martin-Zambito Gallery in Seattle, a gallery devoted to Pacific Northwest art history and the work of early 20th century American artists who, for one reason or another, are forgotten or were never given their due in the annals of art history.

Martin will be a guest speaker at the Thursday evening event.

“Current art history has not given the Camffermans proper credit,” Martin said.

He cites artist Mark Tobey as the one given credit for being the first accomplished abstract artist from the Northwest, but Martin disagrees with the history books.

“Peter Camfferman’s work was far more advanced than Tobey’s if you compare the two in the 1930s, as was Margaret’s. But art historians have never even written about Camfferman and nobody knows how great he really was.”

Martin said a lot of that has to do with reputation and how socially driven the art world has always been.

The Camffermans were immersed in their art, not in the business of marketing themselves to the “in-crowd.”

Indeed, Brachenwood was on an island that not many people took notice of in those days.

The Camffermans had purchased property from Coe in the area that now surrounds Brackenwood Lane, but both painters had come a long way both artistically and physically before landing on the island.

Margaret Gove Camfferman was born in Rochester, Minn. and first studied at the Minneapolis School of Fine Arts where she met her husband. Then it was on to the New York School of Applied Arts & Design and then finally, both she and Peter, who emigrated from Holland as a child, studied with Robert Henri in New York and with Andre Lhote in Paris.

Peter Camfferman went on to study with Stanton Macdonald-Wright, developer of the Sychromist movement which aimed to create emotion with color, a form which, Martin said, Peter Camfferman became a master.

“It was the first American abstract movement that influenced the international art world. Peter was the only one in the Northwest doing it,” Martin said.

“His paintings during that period are extremely vivid, with very saturated colors. The whole movement of modern art is reflected in the Camffermans’ work and it’s in high contrast to where they were living,” he added.

Whidbey Island was not the center of the art world, but it is where the Camffermans would remain.

The two settled in Langley and set about establishing a colony of small cabins and studios where visiting artists could stay, be inspired by their surroundings and paint in the company of their peers.

The Camffermans were some of the earliest modernist painters in the Northwest and were part of Seattle’s Group of Twelve.

They also had close ties to the Women Painters of Washington, as well as the Puget Sound Group and the art faculty and students associated with the University of Washington.

At Brachenwood, they offered classes that were frequented by many of the painters of the Northwest.

But it was also where, together with the gracious Coe and Margaret’s sister Helen Gove, the Camfferman’s reveled in the arts, putting on plays with the family and tending to the elaborate flower gardens and orchard that became the subject of many paintings.

The colony had flourished from the 1920s until 1957, when Peter died and the studios began to fall into disrepair.

Bob Waterman of the Langley Historic Preservation Commission will speak about the Camfferman’s colony.

Waterman and his wife happened to purchase one of the plats of Brachenwood that was eventually divided and sold for residences years after Margaret Camfferman’s death in 1964.

“We have sent out a special invitation to those people who lived in the colony buildings after the artist colony closed down to come and tell their stories,” Waterman said.

The place, for a time, was said to have become a kind of low-rent “hippie haven,” according to an Oct. 8, 1991 Record article entitled “End nears for art colony.”

The legacies of artists survive if they have inheritors to tell their stories.

But, Martin said, the Camffermans never had any children and that is one of the main reasons why they are virtually unknown today among art curators.

There was no family interest to share their history.

He would like to change that and hopes to catalogue the Camfferman’s work in an art book, something he already has done for the forgotten women painters of Washington state. (Martin curated an exhibit at Whatcom Museum of History & Art with a catalogue entitled, “An Enduring Legacy: Women Painters of Washington, 1930 – 2005.”)

“They weren’t people who honked their own horns. They lived for art and liked to stay near their gardens on the island,” he said.

Despite the lack of renown today, both artists were recognized during their lives and showed their work in some of the most prestigious art institutions in the country, including the Public Works of Art Project, the Seattle Art Museum, the First National Exhibition of American Art in New York, the Golden Gate International Exhibition, the San Francisco Art Museum, the California Palace of the Legion of Honor and the Smithsonian Institution’s traveling exhibitions.

Martin said he would like to change the history books to include such fine but forgotten artists as the Camffermans and other women artists and artists of color who deserve to be remembered, studied and curated.

The Martin-Zambito Gallery holds some of the Camffermans’ paintings as does the Seattle Art Museum, the Henry Art Gallery in Seattle and the Tacoma Art Museum, as well as various private collections.

“The work that the Camffermans did was advanced for this country. They were very much ahead of their time,” Martin said.