In Puget Sound a few miles west of Oak Harbor are two islands and an aquatic reserve that need special permission to visit.

The Citizen Stewardship Committee, composed of members from Whidbey Watershed Stewards and Whidbey Audubon Society, is one of the few with such access. Without the group, there wouldn’t be any scientific data collected on the thriving ecosystem that is the Smith and Minor Islands Aquatic Reserve.

“Whidbey Watershed Stewards has a contract to conduct citizen science and communicate what we’re doing here,” Rick Baker, chair of the Citizen Stewardship Committee, said. “Part of what we do is raise interest in the area, but a lot of people still don’t even know there is a marine reserve right here on Whidbey. It’s an incredibly rich ecosystem.”

The reserve is the only aquatic reserve that borders Whidbey Island, and is also managed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service as a National Wildlife Refuge. It spans 36,300 acres of tidelands and seafloor habitat, an area that contains the largest kelp forest in the state. The reserve surrounds both Smith and Minor Islands, making human access to the islands limited. Trespassing on the islands can result in a fine, according to Baker. The waters in the reserve are, however, open to the public.

The reserve is protected because the islands and the vast kelp bed provide “critical habitat” for avian wildlife and marine mammals, some of which are rare species. However, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the DNR, which oversees the state’s aquatic reserves, aren’t able to visit on a regular basis.

That’s where the Citizen Stewardship Committee steps in, providing the foot soldiers to track the state of the reserve’s ecosystem.

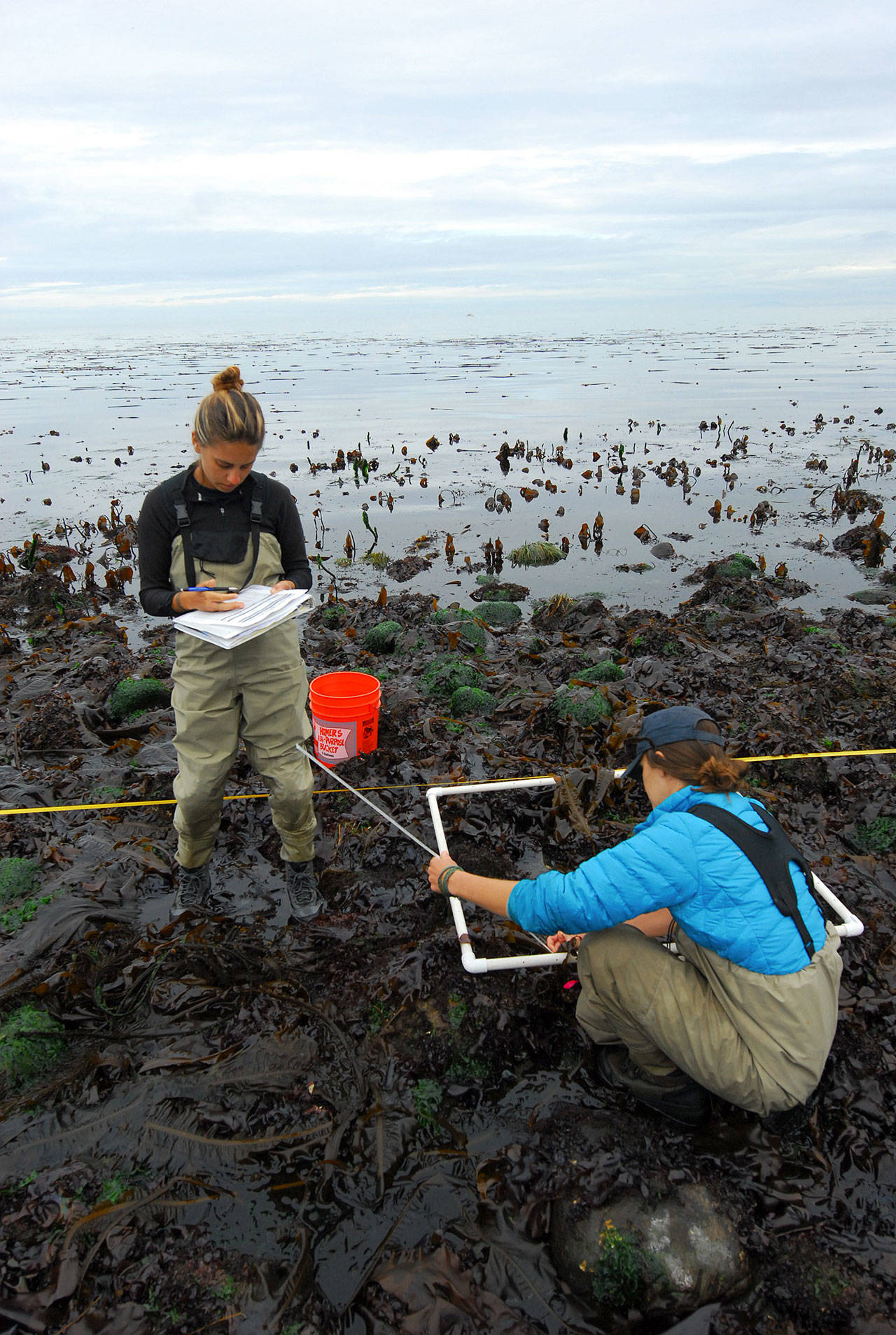

Whidbey Watershed Stewards’ contract to conduct citizen science on the reserve led to the formation of the group. The committee, which Baker estimates has a dozen members, monitors the area’s vast array of wildlife and reports its findings to the Washington Department of Natural Resources (DNR). If anyone is spotted on either island, it’s a good chance it’ll be one of the group’s citizen scientists with a pen and clipboard.

“In most cases, there aren’t a lot of expenses for the work us volunteers do, where with other research it often requires a lot of money to pay for a laboratory,” Baker said. “We’re the cheap option, but we’ve done studies on human use of the shore and nearby waters, the environmental impacts of harvesting the kelp in the reserve, bird studies, you name it.”

Baker is presenting on the aquatic reserve and the Citizen Stewardship Committee’s work to Whidbey Audubon Society at 7:30 p.m. on Thursday. The free discussion is open to the public and located at Unitarian Universalist Congregation north of Freeland. During the presentation, Baker will make his “sales pitch” about the reserve and the citizen scientist group in an effort to add a few more members to the team.

There is also a chance to see a fraction of the aquatic reserve in a half-day field trip on Saturday, Nov. 11. Steve Ellis, vice president of Whidbey Audubon Society, will lead the trek along Whidbey’s western shore, a border for the aquatic reserve. Ellis is also a member of the Citizen Stewardship Committee. The field trip group will meet at 9 a.m. at the end of Libbey Road in Coupeville; participants won’t go to the islands but will explore the shoreline.

According to Baker and those who look over the aquatic reserve, piquing interest in the area is crucial as valuable federal grant money from the federal Environmental Protection Agency has been cut. Work conducted on the reserve will likely become even more reliant on volunteer work.

“The Citizen Science Committee is on the defunded list, so they’ll have to recruit more volunteers from here on out,” Susan Prescott, Whidbey Audubon publicity chairwoman, said. “I know the citizen science they do is important, and they plan to continue funding or not.”

Baker, Ellis and other volunteers are determined to keep up their research regardless of funding. It’s particularly important, Baker says, as “external things are changing in the region and around the world.” The work conducted on the reserve documents the state of the ecosystem, and the group says that data could be useful for scientists in the future.

Without them, that data wouldn’t be around.