Ever since the Ice Age glaciers retreated, humans surveying our Rock have thought up some really big dreams to populate the place and make it famous. I’m sure the original indigenous peoples setting foot for the first time thought, “Wow, what a great place. Let’s invite the whole tribe to fill it up!”

The European American settlers in the mid-19th Century eagerly urged everybody they knew to quickly make land claims to join them in creating new wealth here. The Deception Pass bridge was an extravagant idea by the mainland powers-that-be to make it easier to get here. Perhaps the most successful big dream so far came when the Navy managed to turn a tiny seaplane base from 1942 into a 21st Century training site and home base for thousands of jet pilots.

But along the way there were many, many other big dreams that failed and are now mostly forgotten. Here’s one: some mainland dreamers after World War II decided we should eliminate ferries and build bridges all across Puget Sound. Most notably a bridge from Mukilteo to Clinton that undoubtedly would have turned our Rock into a Seattle suburb. Aren’t we all happy that one died?

Then there was Little Chicago. Heard of it? Neither has anyone else beyond the most avid students of Rock history. Little Chicago was a bad big dream launched in 1890 that died a decade later at a place we now call the Keystone Spit, just down from where the Coupeville ferry dock sits.

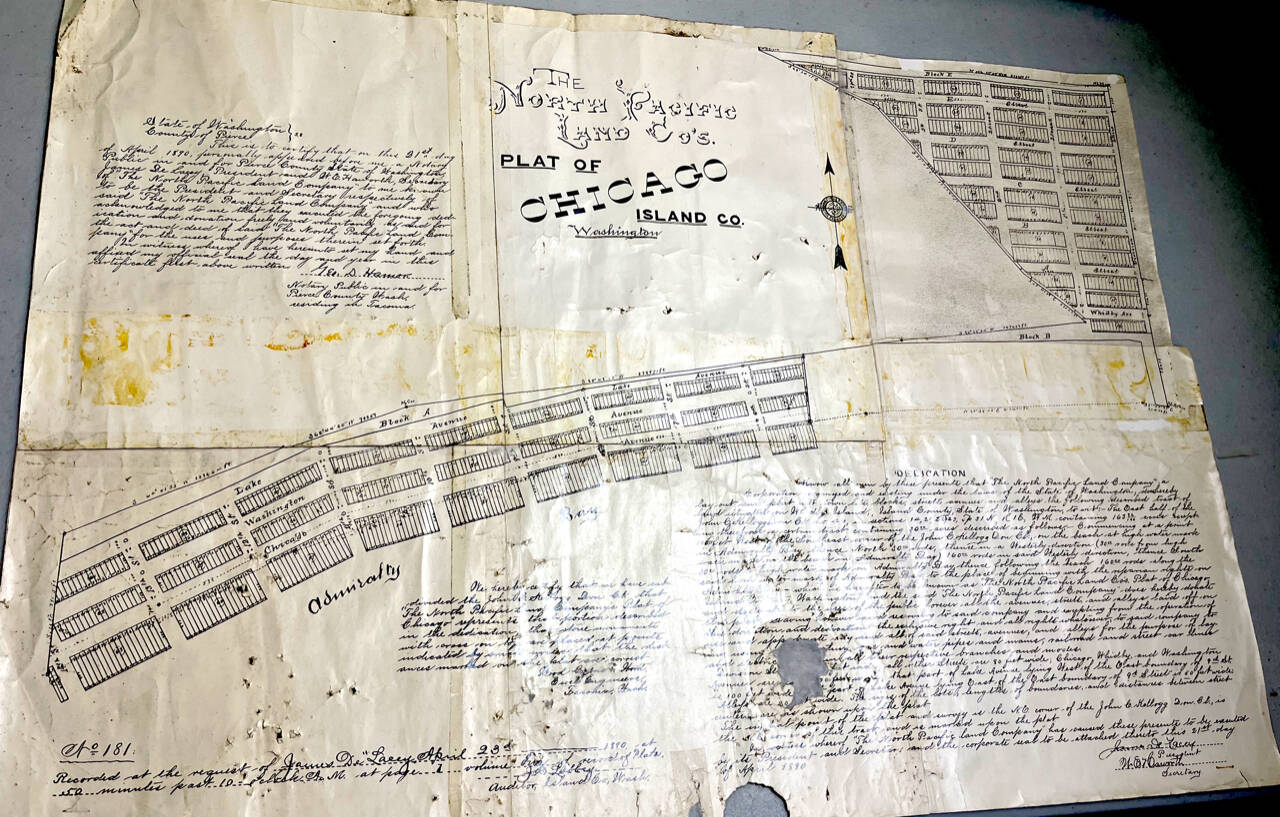

Here’s the condensed version of an amazingly interesting big bad dream. By 1890, Port Townsend had been designated as the western terminus of the brand new Northern Pacific Railroad. A giant land boom set in. A group of Port Townsend businessmen established the North Pacific Land Co. with an eye to extending that land boom to Whidbey as well. With investors, they bought the strip then known as Admiralty Head. They filed a plat map with Island County showing more than 500 individual building sites, with lots to be sold from $50 to $100 each.

North Pacific Land promoted the dream. It began a weekly ferry service from Port Townsend to the new development site, which they dubbed “Little Chicago.” The real Chicago in Illinois was the the eastern terminus of the Northern Pacific Railroad …get the joke? The ferry would bring passengers over on Sundays to inspect the lots for sale, maybe have a picnic and take a stroll on the Crockett Lake Bridge, which had been built in 1888 by another Port Townsend businessman with a big dream for Whidbey. (A few pilings from that bridge, which fell into disrepair and was abandoned by 1910, are still visible sticking out of Crockett Lake today.)

In the first couple years, a number of homes and businesses, and a notorious tavern called The Stump, were built. There was talk that perhaps a spur of the Northern Pacific Railroad would be extended by bridges from Port Townsend across Whidbey and to the mainland.

But then came the catastrophic economic panic of 1893. The nation entered a severe depression. North Pacific Land Co. went broke. And the Northern Pacific Railroad decided to change its western terminus to the rapidly growing city of Seattle, thus crushing Port Townsend and its boom.

Little Chicago was propped up for a few years as Fort Casey was built between 1897 and 1900. It provided employment for virtually everyone living in the area, and more houses were built. And The Stump became the hangout for construction workers and soldiers alike — until it all ended on Dec. 8, 1904, when a guy named John Dollar was shot and killed in a fight at the tavern. The commander of the fort put The Stump and Little Chicago off limits to soldiers and eventually built a fence to keep them from wandering over there.

Within another few years, Little Chicago started looking very shabby with a lot of abandoned homes and businesses. By the 1920s, the dream was over.

Today, about the only way to explore Little Chicago is at the Island County Historical Museum in Coupeville. It has the original, county-approved plat map all written in beautiful cursive writing. It also has a remarkable relic: a short wooden street sign with the still legible words “Chicago Ave.” etched into it despite years of sand, sun and weather. It undoubtedly sat originally on what today we call West Keystone Avenue.

In the years since Little Chicago was forgotten and its shabby abodes demolished, Keystone Strip has added a modest number of new homes. A dozen or more, not 500. And no notorious tavern nearby. That seems like a dream much better suited to our Rock.

Harry Anderson is a retired journalist who worked for the Los Angeles Times and now lives on Central Whidbey.