In the past three years, the amount of stuff from septic tanks and sewage treatment plants making its way to Island County’s treatment facility has doubled in volume.

Since the plant was at capacity, county officials have decided it is time to expand.

While officials in the city of Oak Harbor are building a $100-million or so sewage treatment plant in the middle of the city, county officials are quietly moving ahead with plans to enlarge a smaller sewage treatment plant that most people don’t even know exists. The project is estimated to cost $2.3 million.

The treatment plant is located in the back of the county transfer station near Coupeville. Joantha Guthrie, the solid waste manager, explained that the plant accepts septage from companies that pump septic tanks on the island, as well as effluent from the Town of Coupeville’s sewage plant and the Penn Cove and Holmes Harbor sewer districts.

The companies and entities each pay a fee to dump their sewage.

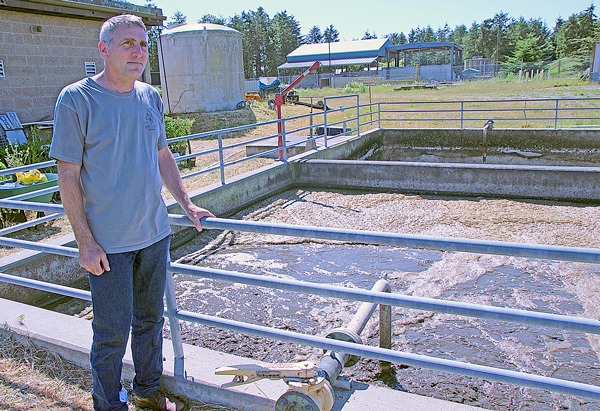

Joseph Grogan, plant operator, explained that trucks carrying the lumpy brown liquid connect to the headworks, which screens out the lumps. The water goes to one of two aerobic digesters, where warm air is pumped in and the bacteria breaks down the unwanted materials.

Afterward, the water is pumped to a lagoon, where the solids settle to the bottom. The lagoons are emptied once a year.

Grogan explains that the de-watered stuff is considered “class B” material. That means local farmers can — and do —use it to spread on fields for hay for cattle.

“They get free fertilizer and soil analysis,” Guthrie said. “It saves the county from having to truck it off the island.”

Grogan said the material tests good enough to be “class A” which is safe enough to spread on gardens, but the county’s permit only allows it to be used as “class B.”

The plant has surprisingly little odor, which Guthrie said is due to a biofilter.

The project, Guthrie explained, will update the screens in the headworks, add two additional aerobic digesters, and expand the lagoon to twice its size. The project is designed and is about to go out for bids. Once done, it should be large enough to last for the next 20 years, she said.

The treatment plant is currently handling about 300,000 gallons a day, which is about at capacity. Grogan said the amount of stuff coming into the plant has sharply increased. In fact, it’s doubled in the past three years.

Bad jokes aside, Guthrie posited that the reason for the sharp increase in the amount of septage from Whidbey residents has more to do with the economy and less to do with people’s diets.

She said more people are trying to sell their homes in the incorporated county, which means they have to get their septic tanks pumped.

In addition, Public Health has been urging and educating residents about getting their septic tanks inspected, she said. As a result, there’s more pumping going on.