The price tag for sewers in Freeland’s commercial core could hit $9.4 million, and monthly bills for customers may be the highest on Whidbey Island, according to preliminary cost estimates.

Gray & Osborne, Inc., a Seattle-based engineering company hired by the Freeland Water and Sewer District, recently presented a report to district commissioners that broke down cost estimates for different scopes of the proposal, along with monthly charges that would fund maintenance and operation of a new sewer treatment facility. The report calculated a total project cost of between $8.7 and $9.4 million, and monthly use charges of $78 or $97.

The difference between the estimates are based on the possibility of the Main Street Sewer District merging with its larger Freeland counterpart.

Hoping to pay for the bulk of the project with grant funding, Freeland district leaders said they were satisfied with the estimates, and cited the monthly charges as fair.

“I feel it’s reasonable,” said Lou Malzone, president of the district’s board of commissioners.

The monthly charges, which are the base rate for a single equivalent residential unit [ERU] — about 6,000 gallons a month — were also estimated on the high end, according to Andy Campbell, district manager. In other words, it’s very possible the cost would be significantly lower once the final numbers are hammered out.

“It’s a very conservative estimate, so it could be a lot less,” Campbell said.

Happy to pay a premium

As it stands now, however, the estimated user charges would be among the most expensive on Whidbey Island. A comparison by the South Whidbey Record found that $97 would top bills for the same amount of use — 6,000 gallons per month — in Langley [$61], Coupeville [$48] and Oak Harbor [$89]. Even the lower rung estimate of $78, the cost if the Freeland and Main Street districts merged, would exceed all but Oak Harbor’s rate.

Those monthly charges would pay only for regular maintenance and operation. An estimated 81 property owners in the commercial core would have to split whatever is left over of the total project cost that isn’t paid for with grant money.

Despite the higher rates and a long-term construction bill, few have come forward to publicly condemn this latest machination for Freeland sewers. Many seem either supportive, or have yet to make up their minds.

Steve Myres, a commercial property owner on Harbor Avenue, said he’s always been in favor of sewers and that it’s a project decades overdue.

“I’ve been wanting sewers in this town for a very long time,” he said.

Myres said he is happy the current commissioners, two of whom — Malzone and Commissioner Marilynn Abrahamson — were adamantly against a 2010 $40 million version that would have sewered the greater Freeland area, have taken on what has been an unpopular and controversial infrastructure project in the past.

Myres added that paying a premium for monthly sewer service would be of little consequence when faced with more expensive alternatives.

“When you look at the cost of replacement [of a septic system], $100 a month is a non-starter,” Myres said.

Another Freeland commercial property owner, Jim Porter, is still on the fence. He said sewers could result in many positives for the area, such as improved water quality and stirring economic development, and those can’t be ignored, but he’ll see little direct benefit. For him and many others, it’s going to come down to one thing — dollars and cents.

“The first thing is, what’s it going to cost,” Porter said.

Project funding options

Knowing how much sewers will cost individual property owners won’t be known for some time as it’s dependent on how much of the project is paid for with grants. The district has more than $3 million already squirreled away from a past grant, but it expires next year, which puts the project under a time crunch.

Myres complained that the district has already had to return over $5 million from earlier grants, and he worries this will be lost too if the project doesn’t make the deadline.

According to Malzone, there’s still time and he also hopes to hit up Island County for an earlier promise to provide $100,000 per year for the next 20 years. Combined with additional grant funding possibilities, he’s hopeful only a small portion of the bill will be left for Freeland property owners to pick up.

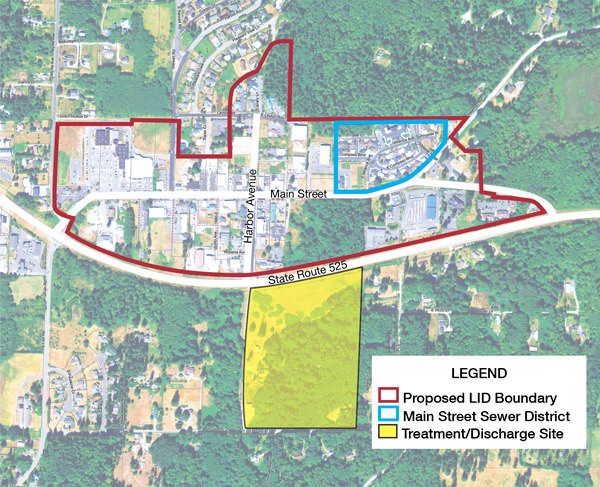

Whatever that number is, the tab would be applied only to those within the commercial core boundaries, an area stretching from Windermere to the intersection of Main Street and Highway 525. It would not be split evenly, but would be based on the special benefit earned by individual property owners.

For example, some property owners might pay more because sewers would turn their drain fields into valuable commercial property that could be developed, while people such as Porter, who has a drain field so close to the highway that it can never be developed, might pay less.

That bill would be applied over a period of decades, and may be paid for through the creation of a local improvement district, or LID. They can be created by vote of the Freeland commissioners or by petition of affected landowners. Malzone said he would only support the latter. He believes in the project, but this is a decision that must be made by those who will foot the bill.

“I can do it by law, but I ran on a platform that I would not do that,” Malzone said.

“It’s up to the property owners,” he added.

More hurdles ahead?

That’s something of a matter of opinion, however, as county officials say state law may be less accommodating. In a June 18 letter to the water commissioners, Brad Johnson, a senior planner with Island County Community Development, called the district’s plan “unacceptable.”

“… the proposed amendments do not prescribe a plan for achieving comprehensive, UGA [urban growth area] wide sewer service within a 20-year period; rather, the proposed amendments would break the proposed sewer plan into five phases and construct only the first phase over a 20-year period,” Johnson wrote. “This phasing plan is unacceptable.”

The Freeland water district already has a sewer plan in place, adopted in 2005. It was amended in 2010 — the $40 million plan — and district commissioners hope now to amend that proposal again detailing the construction of sewers in just the commercial core.

Johnson and department Director David Wechner maintain that such a modification leaves out residential areas that the Growth Management Act of 1990, landmark legislation that guides modern development, say must be included.

“So when do these happen,” said Wechner, of nearby residential areas. “That’s the question.”

“The problem is one of timing,” he added.

But Malzone interprets the act differently, saying it doesn’t require the commissioners to take action, only make plans. The district must have a written document outlining a way to build sewers, but it doesn’t have to force anyone to pay for it.

“We’re required to plan for growth and that’s what we’re doing,” Malzone said.

Similarly, Gray & Osborne project engineer Eric Nutting said the district and county can “sit around and wink at each other and say, ‘We’ll do it all in 20 years,’ ” but this proposal is a realistic way of taking the first step, which is the most difficult.

“What we need to do is start; that’s the hardest part,” Nutting said.

Johnson said the state’s rules exist for a reason, and that’s to ensure adequate services and infrastructure are in place to support developed areas.

“It would all be pretty absurd if it were just about creating plans,” Johnson said.

County officials contend that despite the water district’s autonomy, the Freeland urban growth area is part of rural Island County, which makes the county ultimately responsible for appropriate growth.

“We’re the ones who get the enforcement order,” Wechner said.

The department has other concerns about the proposals meshing with existing long-range county planning documents, such as the comprehensive plan and Freeland sub-area plan. They all need to be consistent. Finally, planners have technical concerns about the district’s plans to site a treatment plant on the same property that’s home to the district’s primary wells on the south side of Highway 525, across from Harbor Avenue. Wechner and Johnson said discharge plans for the property have yet to be made clear to the planning department.

Despite the county’s numerous concerns, Wechner, Johnson and district leaders are all hopeful the issues can be resolved through collaborative discussion. A private meeting between the parties, including Gray & Osborn engineers, has been set for next week.