Activists concerned about Navy jet noise decided they weren’t done grilling the Island County Board of Health.

Members of the Citizens of Ebey’s Reserve, or COER, returned in force for the second time Tuesday, bringing a list of actions they think the board should take and some tough words for public officials they say aren’t listening to their constituents.

The group attended the board’s April meeting, voicing ongoing concerns about jet noise.

Ken Pickard, president of COER, encouraged the board members to find their “courage and ethics” and put aside “your addiction to Navy dollars and patronizing attitudes.”

More than 20 activists filled the folding metal chairs at the monthly meeting, held in Coupeville. They hung laminated signs about the dangers of jet noise around the room. They sharply shared their concerns about health impacts as well as, in some cases, the details of personal medical problems they say are caused by the rumble of the Navy’s EA-18G Growler, which takes off from Naval Air Station Whidbey Island and practice carrier landings as an airstrip near Coupeville.

A Coupeville teacher said it was so noisy teachers had to stop speaking when jets flew over. Another woman was upset because it was so loud over her mother’s North Whidbey home, emergency responders couldn’t talk to each other when they were trying to help after her mother suffered a stroke. A Coupeville woman told the board the jets frightened her miniature Schnauzer and it ran into the woods and was lost.

A handful of Navy supporters showed up too, including military jet superfan Joe Kunzler, who wore a Growler T-shirt and brought a video camera to record the meeting. He read a letter from a retired Navy officer who wrote he was angry to the “C-O-R-E” that some people from “C-O-E-R” were blaming the military when they choose to live under the flight path. Another person who addressed the board suggested the protestors accept the situation because the alternative to jet noise in the middle of the night might be a call to Muslim prayer.

Some of the elected officials took their lumps better than others.

Oak Harbor Mayor Bob Severns, who serves on the board, immediately asked the public comment period be moved to the end of the meeting, since he needed to get to another meeting later that afternoon. The board decided instead to limit comments to 30-minutes total, with each person limited to 2 minutes.

Board member Grethe Cammermeyer apologized for not being as respectful as a listener as she could have at the last meeting. She acknowledged that the board as a civilian entity might have little it could do to influence the military, but she expressed interest in exploring any possible solutions.

Island County Commissioner Jill Johnson pummeled county health officer Dr. Brad Thomas with so many questions about whether jet noise is directly linked to health problems that her colleague Commissioner Helen Price Johnson asked if she was finished so the meeting could adjourn.

Thomas said noise could be a risk factor in various health conditions and that unlike some choices such as smoking, people who lived around the base and the airstrip didn’t get a say about it.

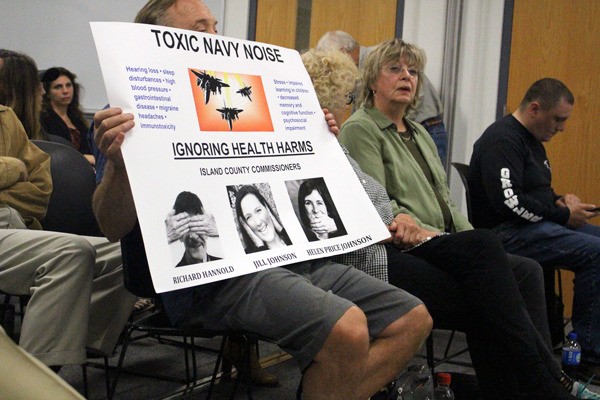

Part way through the meeting, the activists pulled out signs that had hands digitally-added over photos of the three county commissioners, depicting them as the monkeys who “see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil.”

The officials attempted to carry on the meeting as if nothing was happening, as the activists glared and held the signs.

The activists presented the board with health studies and a list of actions they could take. Their suggestions include posting signs in public places that warn people in noisier locations to wear protective hearing equipment and closing some public parks during flight operations, including Rhododendron Park, the Central Whidbey Youth Athletic Field, Admiral’s Cove Beach Club pool and Camp Casey. They also said the board could request reimbursement from the Navy for all costs associated with public mailings, postings and hearing protection for the public.