They were friends, brothers and sons.

They were students, athletes and South Whidbey High School graduates.

They had hopes and aspirations that will never be actualized — cut short by tragedy.

Marcel “Mick” Poynter, Charles “Mack” Porter and Robert Bruce Knight are missed by those who knew them.

Robert Bruce Knight

Rob Knight lived like a running back.

He envisioned the end zone — the goal — and he made his way there, no matter what got in his way.

Knight was 22 when he died in a car crash just after midnight, in the earliest minutes of Nov. 12, 2011.

The 2007 South Whidbey High School graduate was a renowned fullback for the Falcon football team. In his senior season in 2006, Knight had 246 carries for more than 1,500 yards. That season he was voted the Cascade Conference Offensive Most Valuable Player.

Though he was more than a football player — he also loved music and played guitar and drums, which he first made out of buckets, pans and pots — that’s where he triumphed, said his parents Sharon and Bruce Knight.

“That’s where he was the happiest. He was self-actualizing at football,” said Bruce Knight, who was the Falcons’ running back coach during his son’s two seasons at South Whidbey.

From the sidelines, he watched his son return from two months at Red Cliff Wilderness Therapy Camp in Utah to carry the ball on the first play of his senior season. That one play left Knight’s dad grateful to Falcon co-head coach Mark Hodson for giving his son a chance, and allowing him to be there for it.

“It is his story,” he added. “That one moment represents probably one of his greatest achievements ever.”

The run, though not a 40-yard sprint to the end zone, represented his ability to set a goal, make a plan and follow it through.

That first carry his senior season, after all, was what got him on track and got him out of Utah.

His parents sent Knight to the outdoor therapy class to get him grounded. While there, Knight learned ways to focus on academics and respect himself and others. Along the way, he earned an “earth name” — Watchful Otter — which his parents said embodied his playful, loving spirit.

Then they sent him to boarding school in Provo, Utah. He needed support his parents couldn’t give him, and they tried lots of methods.

“We exhausted every resource we could exhaust to get through all this,” his dad said. “He went to boarding school, and he realized at that point he had to accomplish a whole bunch of things to get back to where he wanted to be. And that was playing football at the high school.”

Knight was living on South Whidbey the past year. Prior to that, he was enrolled at Pacific Lutheran University in Tacoma and playing for the Lutes football team. A meniscus tear ended his season and Knight dropped out after his first semester in 2008.

His dream to keep playing football continued though as he played for a semi-professional team, the Bellingham Blitz. Injuries had not kept Knight out of action in the past, and they weren’t going to sideline him then, either.

He was raised for most of his life in Canyon Lake, Calif. He grew up with one sister, Jamie Metcalf, and one “sissy,” Lisa Zickafoose. Zickafoose was a sister through residence, who lived in the Knight home for a time.

Being 11 years older, Metcalf did a lot of babysitting for her “Bubba,” her nickname for Knight.

Metcalf, now married to Dusty Metcalf and raising two toddler sons of 22 months and 3 years, remembered her brother being gentle and affectionate – a “sweetheart.”

“We had caught a fish, and we were so excited,” Metcalf said. “We had pulled it on the dock and it was flopping around. We were both screaming and panicked. He said, ‘Get it off. Get it off. Help this fish.’”

She bit the line and tossed the fish back in the lake.

Knight wondered if the fish would be OK, and his sister told Bubba it would be fine as the fish swam away.

The little boy offered his sister a thought.

“He goes, ‘I think his sister is going to come help him,’” Metcalf said.

As a fifth-grader in Canyon Park, he broke his ankle playing on a rope swing. After having a cast set on his ankle, his mother thought it would slow him down. She was wrong.

A fellow teacher told her Knight was playing kickball on crutches.

“He’s out there on his crutches, crutching around the bases,” she said.

He actually made it pretty far before he wiped out, his mom said.

“He was a gift,” his mother said.

She remembered a time they were sleeping in a tree fort at their Canyon Park home. He was younger, maybe 8 years old. She said they didn’t talk much, and they sang “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star,” after seeing a shooting star streak across the clear Southern California night sky. She smiled.

“Rob to me was kind of a shooting star,” she said.

Charles “Mack” Porter III

Charles “Mack” Porter III was a new face among lots of lifelong Whidbey Island students when he first moved to South Whidbey in 2009.

He was looking for a new start, and was a bit of a fish out of water on the island. Porter came from Palmdale, Calif., a city 60 miles north of Los Angeles with more than 150,000 residents, to an island where the only incorporated town on the South End doesn’t have a single stoplight.

One of the first friends he made was Marcel “Mick” Poynter, who also died in the car crash last weekend. The two spent most of their time together.

“Mick and Mack were pretty inseparable,” said Mike Berry, their former youth pastor at Christian & Missionary Alliance Church in Langley. “They would just play off each other so much.”

Where Poynter was known for being boisterous, Porter was reserved.

One friend, 16-year-old Jake Sladky, spent a lot of time with Porter the past few months, often sitting together and talking while watching Poynter skate at South Whidbey Community Park.

“Mack wasn’t one of those people who would talk a lot,” Sladky said. “He didn’t want to be the center of attention.”

“He was a little more serious than Mick,” Berry said.

Sladky met him in August when Porter moved back to Whidbey from Southern California. Sladky and Poynter were friends, and he often heard Poynter tell stories about Porter and share how he was excited for him to be living on the island again.

“Mick would always talk about him,” Sladky said.

Porter enjoyed being with friends, even if he wasn’t the loudest one or best-known among them. In groups, he could become quiet until the perfect moment.

“He’d wait for the perfect moment and say something just hilarious,” Berry recalled.

Together, Poynter, Porter and Sladky spent most of their free time with each other. They would go the skate park, they watched TV, they talked and they played video games like “Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2.”

Watching, and hearing, Porter play the first-person shooter game was quite a sight.

“To watch Mack playing Xbox — both Mack and Mick — Mack would just get into it,” Sladky said. “He would just start yelling at the TV. Whenever he died during ‘Call of Duty,’ the face that he would make, he would stick out his tongue or bite his tongue during play.”

Sladky claimed he was the best gamer among the trio, and said Porter wasn’t much of a gamer beyond “Call of Duty.”

“He was not a big gamer,” Sladky said. “He just liked to yell a lot at the TV.”

That was the rowdy side of Porter. His friends said he was quiet, to a point, but was the first friend to back them up or help them when they were in trouble.

“He wouldn’t back down to anything,” Sladky said.

Porter was an amateur mixed martial arts fighter in California. Sladky said he only had two fights, both losses, and Porter had a good sense of humor about the defeats. He aspired to train again to fight in Washington.

“The first one, he got his butt kicked in like the first round,” Sladky said. “In the second one, he made it to the second round, but he told me was just so exhausted that he couldn’t hold up his fists and got shot, then they took it to the ground and he just got wailed on.”

“He loved it,” Sladky added.

Berry experienced a gentler side of Porter as his youth group leader. Porter was in the Young Marines and put in more than 3,000 volunteer hours with various children’s groups.

“I got to know a side of Mack that probably not too many people other than his close friends and the family he was living with up here knew,” Berry said. “He just had a huge, huge heart for mentoring kids.”

When Berry saw him around the school during sporting events or around town, Porter would embrace him.

“He’d always go out of his way to give me a hug or a handshake and tell me how things were going,” Berry said. “He was just a really genuine young man.”

His friends remarked about his smile. Like his general demeanor — quiet and reserved — Porter’s smile was slight, more of a grin or a smirk.

“He would always have a little smirk on his face,” Sladky said. “But when he looked at you, it would be an ear-to-ear smile. It was just a grin. That’s something that I’ll never forget about him.”

“Not a lot of people got to know him, which sucks because he was a great guy,” Sladky said. “He’s one of the nicest guys I’ve ever met.”

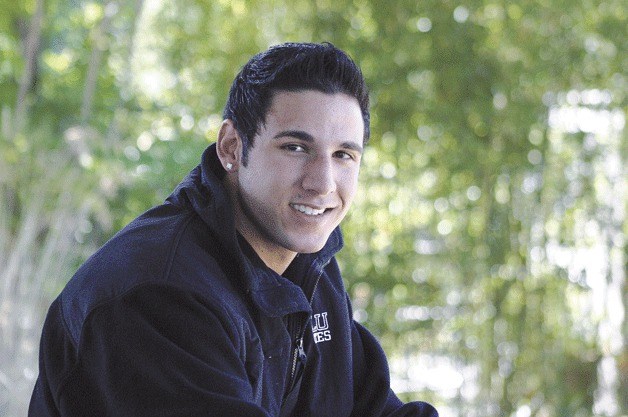

Marcel “Mick” Poynter

Marcel “Mick” Poynter was an avid baseball player with plans to play for the team at Shoreline Community College. But he had other interests beyond baseball, most recently, as a new business owner and T-shirt designer.

His friends, former teachers and coaches remember plenty about Poynter, a Langley resident.

One friend, 17-year-old Molly Rawls, has grown up with Poynter at her house. He was close friends with her brother, Trapper.

“At one point he brought over his own Xbox and TV so he could play next to my brother, because he wanted to be able to play in the same room,” Rawls said.

Poynter loved being with his friends, and he loved to compete.

Dave Guetlin knew Poynter as a player in South Whidbey Little League and coached him in high school; Guetlin’s son graduated the same year as Poynter.

“The one thing about Mick was, I don’t think there was a baseball game that he played in where he didn’t get dirty,” Guetlin said. “He was one of those scrappy kids where he was always trying to get an extra base or always trying to do something to help the team out in some way.”

“I loved his competitiveness and his drive.”

That meant a bit of drama at times, he added.

“Probably the biggest thing I think I’ll always remember about him is how much of a competitor Mick was,” Guetlin said. “He just absolutely hated to lose a game.”

“If he made an error, boy, that glove would come slamming down and onto the ground. We called it the Flying Mick Poynter Glove Slam,” Guetlin added.

Making jokes at his own expense was one way he got laughs and made friends. Berry, his former assistant coach and youth pastor, remembered Poynter tucking his ears, which he called “really big ears,” into his hat.

“Then his smile would pretty much cover his whole face,” Berry said.

Poynter’s smile was almost as well-known as his ears, or his famed flying glove.

“He was just that loud, happy-going kid who walked through the halls with a smile on his face,” Rawls said. “He had so many friends with so many different groups of people and everyone knew who he was.”

Poynter was also a budding entrepreneur. He had just started a T-shirt design company, called Western Empire Clothing, in August. And he recently collaborated with Zach Broyles, a fellow South Whidbey clothing designer, on a joint line of shirts.

“He definitely had a talent for designing,” Broyles said. “His heart was in it.”

Even so, baseball was his true passion and pursuit.

Guetlin saw Poynter at the start of the school year in September and spoke with him about playing baseball at Shoreline Community College.

They talked about baseball a lot.

“Mickey Mantle was my idol growing up as a kid, so I always talked to Mick about that,” Guetlin said.

Berry recalled those many bus rides home from Sultan, Lakewood, Cedarcrest and the other Cascade Conference schools, when Poynter would sit near the front of the bus to speak with coaches and ask what could be done differently, how could he improve.

“Looking back, I really cherished those times,” Berry said.