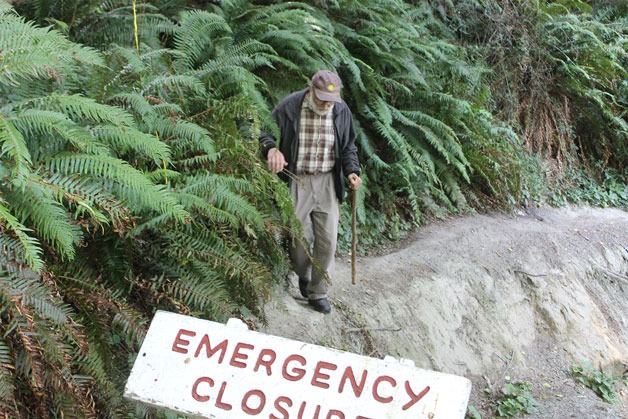

The sign that reads “Temporary Emergency Closure” at the entrance of South Whidbey State Park’s beach access trail is one Greenbank resident Michael Seraphinoff has taken a disliking to. Storms in December 2015 and January 2016 damaged the midpoint of the trail while also wrecking a wooden stairway that leads down to the beach. The result: no beach access.

“There’s no evidence that there’s anything very temporary about it,” Seraphinoff said. “There’s much more evidence that there’s no money, and there’s no priority to fix it.”

South Whidbey State Parks is currently in a battle against nature as wet conditions have continually damaged the beach access trail. The state park is located on an active bluff and is prone to landslides, said Park Manager Jon Crimmins, making repeated efforts to repair the difficult trail-to-maintain.

“It’s one of those things that when Mother Nature decides, we don’t have much of a say,” Crimmins said. “If it was a money thing, it would be easier. It’s a nature problem.”

Crimmins said that efforts to identify alternative locations for the trail have also been met with failure. Five years ago, parks officials found a suitable location for beach access south of where the stairway is currently located. The project was to include a tower and contain a ramp and spiral stairway. But, just as the project was about to kick off, a landslide led to the area being virtually unusable. It’s one of the many frustrations staff have faced in finding a suitable location, but have not jumped on due to safety issues.

In other words, plans are in a state of limbo.

“I would love for there to be a solution, but again, nobody wants to get into a situation where were putting taxpayer money into something that’s going to fail,” Crimmins said. “Until there’s a viable route down to the beach that we can believe in, that’s where we’re held up.”

Already hampered by tree rot and disease that led to the closure of overnight camping at the Freeland park in the spring of 2015, Seraphinoff said the newest blow is representative of a downward trend in priority for state parks.

“This is a public treasure that is being squandered,” Seraphinoff said. “This park has been known by many, many people as a special place to come and enjoy.”

Though Seraphinoff felt it was the responsibility of the state parks system to make nature available to the average citizen, Coastal Geologist Hugh Shipman with the Washington State Department of Ecology said it’s a problem that is challenging to address.

“I think it’s going to be a difficult area to work within,” Shipman said. “There really is little they can do to prevent this kind of sliding.”

Shipman suspected wet conditions during the winter were the primary factors in the landslides that washed out the midpoint of the trail and stairway. Shipman became familiar with the area while working with the Sound Water Stewards, formerly known as the Island County Beach Watchers, over the years. He said identifying a new area to establish beach access, somewhere that is less prone to landslides, would be a healthy alternative.

“This is an area that has been active in landslides for hundreds, maybe thousands of years,” Shipman said. “So when it gets wet, or ground water levels are high, these slides can reactivate. It’s very unpredictable.”

Sue Ellen White, a former president of the Friends of South Whidbey State Park, concurred with Shipman and Crimmins that the area is inherently unstable.

“If you look at an aerial map, [the land] is curved and slumped,” White said. “It would be prone to a rotational slide.”

White said she would be happy to see the stairway rebuilt, but was wary that the problem may just repeat itself. She also didn’t blame state park staff for not having addressed the problem.

“I certainly don’t fault parks,” White said. “They’re doing the best they can.”

The closure marks the second time in the past decade that residents haven’t been able to access the beach. The stairs were washed out years ago and were rebuilt by a group of private citizens, Seraphinoff said. Now, the top half of the stairway is in a state of disarray.

Beyond the warning sign at the damaged midpoint of the trail, Seraphinoff carefully maneuvered along a thin edge of earth on a sunny Monday morning on July 25. Below, a large chunk of the trail was missing, leaving an exposed cavity of earth. Though the nearly 70-year-old had no problem braving the possibility of falling off the trail, two young women who came shortly before him were not up to the task, Seraphinoff said. He felt the two women turning back could have otherwise enjoyed the park had it not been for the lack of beach access.

“I’m afraid it’s all too common,” Seraphinoff said.

Lisa Kois, co-founder of Calyx Community Arts School, said summer camps held at the state park have also been hampered. Students typically focus on water and tidal lands during the spring and summer months, and without beach access at South Whidbey State Park, Kois said they typically travel to Bush Point as an alternative. Kois is also wary of the danger the area presents. They avoid the area during the winter months due to the danger of landslides.

“For us, we just don’t go there,” Kois said. “It’s just been a reality that we’ve dealt with and tried to work around and keeping hope alive that it will reopen.”

Kois said she’s optimistic state park staff can find a solution.

“I do feel like in this case it’s a balance of what we have to learn from nature,” Kois said. “How do you create a safe route down?”

State park officials are currently working on The Classification and Management Plan, or CAMP, process for three of its properties: South Whidbey State Park, Useless Bay and Possession Point State Park. Crimmins said the management plan will help identify the future of South Whidbey State Park. They are currently focusing on improving day-usage, picnic areas, trails and addressing overnight camping.

“We’re trying to keep it a relevant park and a fun place to visit,” Crimmins said. “It’s a beautiful place, but the amenities are slowly sloughing.”