By 1939, the undisputed sportsman of the decade was not a man. He was a horse and his name was Seabiscuit.

Having beaten 1937 Horse of the Year and Triple Crown winner War Admiral at the Pimlico Special the year before, Seabiscuit was doing some exhibition racing in California to close out his sixth season. That’s when Bob Varner first saw the horse up close.

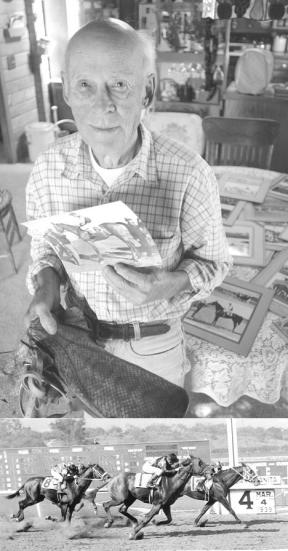

A 15-year-old jockey who was riding by virtue of the fact no one had asked him whether he was of the legal age of 16 to race, Varner — who now at 80 lives in rural Clinton — got his one, brief chance to race against the great champion.

And brief it was. During the quarter mile he raced before his mount came up lame and had to stop, Varner, an experienced rider who had hundreds of wins over the course of a 12-year racing career, lost ground the whole way.

“All I saw was his big, brown butt,” he said.

With Seabiscuit’s story on the big screen this summer as a motion picture, Varner and his wife, Elinor, have been doing a lot of remembering lately. In their Heggenes Road home, they have been paging through a 2-foot high stack of photos of Bob, taken at the wire and in the winners circle after some of his races. They’ve also gone through the scrap book and, thanks to the thoughtfulness of the daughters of Seabiscuit’s late owner, Charles Howard, are now looking for someone to frame copies of a photograph of the great horse with his jockey, George Woolf.

Though to most anyone this journey of memory more than 64 years into the past might seem long, it seems like yesterday to Varner. He’s waiting anxiously for “Seabuscuit” to arrive at The Clyde Theatre on Sept. 12, especially after recently listening to a book-on-tape version of the horse’s life story.

As one a of a very few living jockeys who still remember running against Seabuscuit, he can say with authority that this horse’s story is one that deserves to be told.

“He was a horse that just wouldn’t quit,” he said. “It was always just an honor to run against him.”

But just as resilient and plucky was Varner who, had the timing been right, might have made a perfect rider for the horse against which all others are compared. At 5 feet, 5 inches and weighing as little as 108 pounds when he began racing at age 14, Varner had his share of victories and defeats over the years.

He got his start with race horses as a 10-year-old in Vancouver, B.C., when his father put him on the back of a thoroughbred steeplechase horse at a race track called The Brickhouse. The horse inexplicably ran off, with Varner holding onto the horn of a Western saddle. The ride ended about a mile away at a nearby race track, Lands Down, where the horse had run most of its races over the years.

After that, Varner didn’t go back to horse riding until he was in his teens.

“I thought I was going to die, but I made it,” he said.

When he went into professional jockeying, he knew he had started down a career path with little stability and few guarantees. Racing up to four times a day and generally earning no more than $25 for a winning ride, Varner didn’t make a lot of money. It was more than many others earned during the final years of The Great Depression, but it was hardly comparable to what is earned by top modern jockeys.

The greatest joy in the sport, Varner said, lay in finding a great horse. An independent jockey for hire, Varner rode for dozens of stables, often riding a horse perhaps only once or twice. Though never a leading rider, he had a few excellent mounts. His favorites include the stallion Olympo, astride whom he won at Santa Anita in 1939, and Brown Jade, a mare who had a brilliant career before coming up lame in Varner’s only race with her.

There were also the bad mounts. Varner remembers one horse that threw him in almost every one of about a dozen starts he had with it. He rode the horse to victory once, but that hardly made all the falls worth it.

“I hated that horse,” he said.

Mixed in with all of it was the physical danger of his sport. In one fall with another rider, Jimmy Sullivan, Varner broke his shoulder. But he got the better of it: Sullivan died in the fall as the two jockeys tumbled over one another. Varner would carry that injury — and the wire that held his collarbone together — into three years of Army service during World War II and his brief comeback to horse racing in 1946 and 1947.

Still, as Bob and Elinor Varner wait for “Seabiscuit” to come to Langley, all the memories of those years of racing are welcome. When the movie was first released, Elinor pulled out all the scrapbooks and photos and looked at them for the first time in years. Varner has even pulled down 2-pound snakeskin racing saddle he used during his last years of racing from where it hangs on a wall in his house, just to put his hands in touch with a feeling from the past. The photos and clippings are of somewhat less interest to him — his eyesight has been failing during the past two years, so he can’t see them well.

The couple plans to be first in line at The Clyde on the opening night of “Seabiscuit.” If what they’ve heard so far is an indicator, they believe the film version of their past will live up to their memories of it.