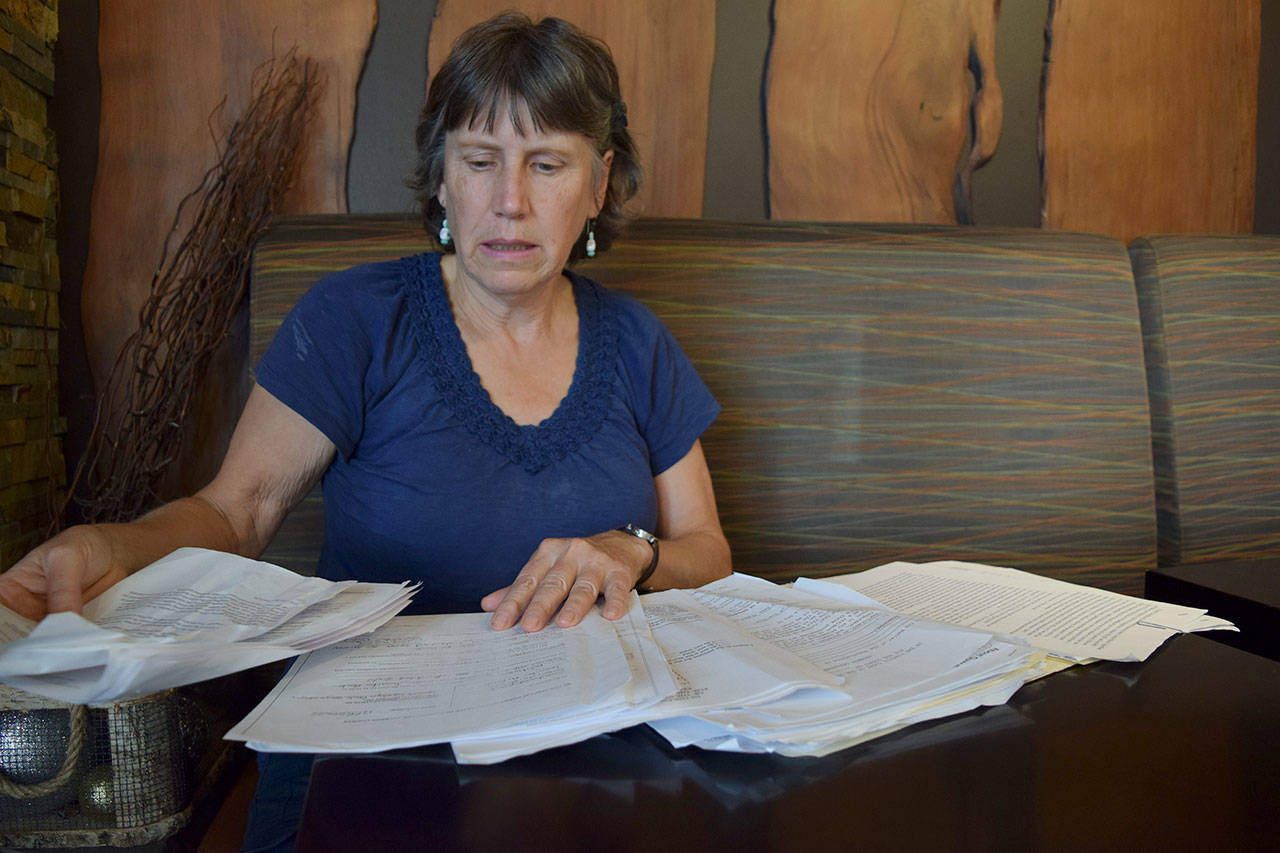

Out of everyone in her family, Freeland resident Carolyn Buck says she is the closest to her developmentally disabled little sister. It’s why she wants to be her guardian.

But it hasn’t been so simple.

Poor planning, legal issues, squabbles over who’s the right person for the job and family health issues have all complicated the process. It’s caused stress in the family and uncertainty about what will happen in the future. Simply put, it’s been a mess, and she worries what will happen to her 54-year-old sister.

“I feel helpless, and I’m just trying to help my sister,” Buck said. “I really hope my story shows guardians they need to work this out before it’s too late, because you never know when that’ll be.”

According to Mike Etzell, developmental disabilities coordinator for Island County, this generation is the first in which children who have developmental disabilities are anticipated to outlive their parents. On top of that, Etzell says societal norms have shifted to where families are raising their disabled children rather than institutionalizing them.

It’s caused new hurdles.

“No other generation has experienced this particular challenge in relation to adult sons and daughters who experience a developmental disability,” Etzell said. “It’s a valid topic in our community especially as we age.”

In order to sort out legal guardianship and a successor, someone has to set it up in court rather than simply writing a will without filing it in court. This is what Buck’s father didn’t do prior to his death, which led to the scramble to make decisions on behalf of Buck’s sister.

When legally obtaining the status, one is required to file a document naming another person as a stand-by guardian. If something happens to the guardian, the stand-by would temporarily step in. Buck’s sister ended up in limbo because a legal stand-by guardian wasn’t identified in case her mother grew ill.

“In the case where a temporary guardian comes into play, the court would likely assign another guardian ad litem,” Freeland-based guardian ad litem Cynthia Trenshaw said. “The stand-by guardian is only a place holder and takes care of immediate needs.”

Trenshaw added it’d be unlikely someone from a group home would be a guardian due to potential conflict of interest. But if someone wanted to become a guardian to avoid such a situation, as Buck is with her sister, one can petition the court, which starts the process with the guardian ad litem.

Trenshaw and Etzell’s general advice: sort the situation out in court before it’s too late, even if it’s a daunting prospect.

Etzell emphasized the importance of developmentally disabled peoples educating themselves if they have the mental capacity to do so. He said guardianship should be the last resort, as it gives people less power.

“Folks really have to investigate and learn about these things because guardianship is the most restrictive option that gives people limited powers,” Etzell said. “People should really consider alternatives if they can.”

But in the case of Buck’s sister, she wasn’t able to select alternatives.

Shayne Nagel, executive director of disability rights charity The Arc of Snohomish County, said there are resources for those in the area with developmental disabilities and their loved ones who can assist with these matters. She recommended checking in with local county disability services, attorneys that work in disability services and guardianship as well as her organization. To her, there’s nothing more important than empowering developmentally disabled individuals to be as independent as possible before deciding to bring guardianship into the equation.

“It really is important for families not to put this on the backburner,” Nagel said. “It’s important to plan and connect with resources and people that can at least point you in the right direction. We always want people to be as independent as possible.”