Unbeknownst to most, the explanation behind the lack of diversity in many Whidbey neighborhoods has been buried for decades in the records of hundreds of properties.

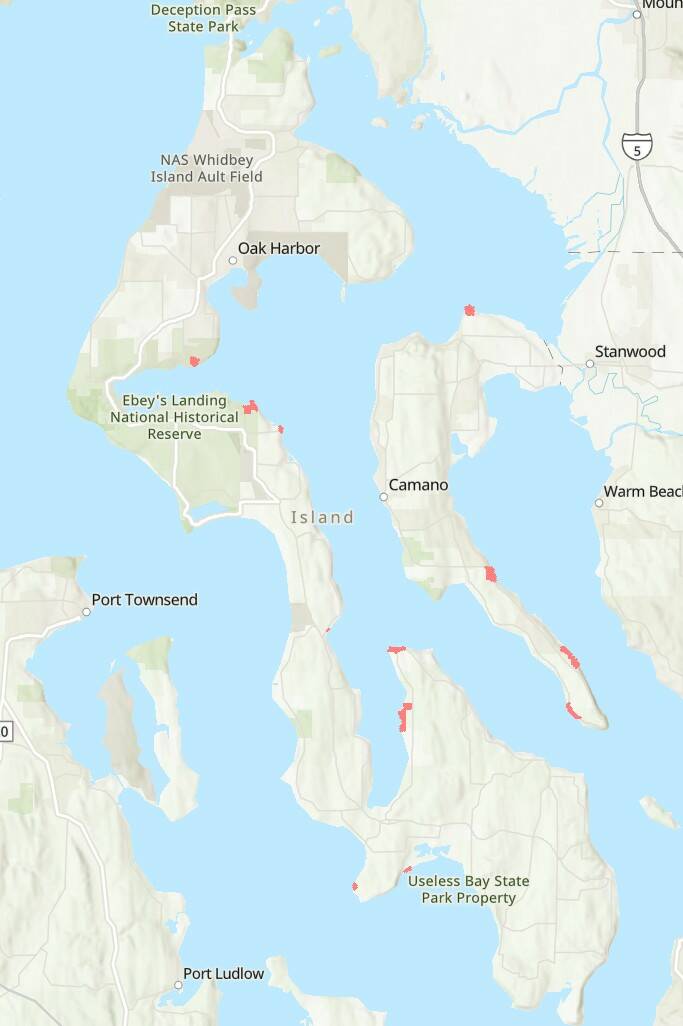

Since 2021, researchers at the University of Washington and volunteers have discovered the existence of 955 racial restricted properties in Island County. While these are no longer legally enforceable, they’re a reminder that Whidbey and the Pacific Northwest were not left untouched by segregation.

The restrictions, which mainly date from 1930 to 1950, were found in the early records of hundreds of parcels and subdivisions located outside of city and town limits. These neighborhoods include Baby Island Heights, Bay View Beach, Beverly Beach, Harrington Lagoon, Mutiny Bay Shores, Penn Cove Park, Greenbank Waterfront Tract and Rhodena Beach, according to the Racial Restrictive Covenants Project website.

Until 1968, these stipulations prohibited properties from being occupied and/or sold to “any person except one belonging to the White or Caucasian race,” with some allowing for non-white domestic servants to occupy the property, as shown in the documents available on the study’s website. Buyers who violated these terms would face litigation.

Project Manager Amanda Miller said current property owners might be oblivious to the existence of these stipulations because they are included in the original documents of their property, which people tend not to read when they sell or buy, even if the new deed is stated to be subjected to restrictions in the original legal agreement.

According to the University of Washington, the restrictions can be found in plats, in a homeowner’s association’s bylaws, in notarized petitions by property owners, as a clause in an individual deed or mortgage, or in documents known as CC&R, which stands for “Conditions, Covenants and Restrictions.”

Restrictive covenants were first established to have no standing in a court of law in 1948 because state enforcement would violate the equal protection clause of the 14th amendment, according to UW. This, however, failed to close some loopholes, with developers still writing restrictions and counties recording them. They finally became effectively illegal in 1968, when Congress passed the Fair Housing Act.

In 2021, Washington passed House Bill 1335, giving UW and Eastern Washington University the task of identifying and mapping neighborhoods with racist housing restrictions across the state. For Island County, where digital records were not available, researchers and volunteers manually inspected archived documents. While the search has concluded for Whidbey and Camano, it’s an ongoing effort in other counties, Miller said.

So far, research associates have found more than 80,000 restricted properties around the state, the majority of which are in the more densely populated areas.

Because these restrictions don’t present any added statements clarifying to new and prospective owners that they are null, they may catch people off guard, Miller said.

While it’s not a property owner’s fault if real estate developers created these requirements decades ago, they have the option to strike illegal and discriminatory language from deeds. To find out if a property has a racially restrictive covenant, people can look into the land title records maintained by county auditors, or check the title insurance policy, which could reference deeds recorded decades before. The covenant modification form and more instructions are available in the “How to file a modification form” page in the Racial Restrictive Covenants Project website.

Through this process, residents can help the islands heal from the past and move towards being a community that values equal opportunities and housing access for all, Rose Hughes said.

Hughes is the managing director of Island Roots Housing, a nonprofit that seeks to create affordable housing in the county. She was the one to bring this study to the attention of the Island County Planning Commission last month while presenting results of a housing survey that she and her team conducted to inform the development of the Comprehensive Plan update.

Island Roots became aware of the UW research just months ago. In an interview with the News-Times, Hughes said most people are surprised to learn of the existence of these restrictions.

Among them is Island County Commissioner Melanie Bacon, who upon finding out from a news inquiry last Wednesday, reacted with a mix of shock and outrage, describing the research findings as “beyond abominable.”

The historic documents show the signatures of previous Island County commissioners and the previous county engineers, treasurers and auditors.

According to Sheilah Crider, the current county auditor, the county’s role is to record documents, and it does not “have the authority to approve or disapprove the content of those documents.”

Still, Bacon would like the county to release a statement of atonement, and if that doesn’t happen, then she will release one herself, as most of the restrictions were found within District 1 (which she represents) and show her predecessors’ signatures, further adding to her frustration.

Visiting South Whidbey, she said, one can’t help but notice the predominantly white population. These restrictions help explain the current demographics and represent an example of systemic racism, she said.

“These are some of the most prime properties on Island County,” Bacon said, pointing out that all the properties shown in the University of Washington’s maps are located by the water. “This was an intentional creation of white wealth in Island County.”

While white families were able to pass down valuable property to their children and so forth, people excluded by the restrictions could not benefit from generational wealth. By the time the Fair Housing Act prohibited housing discrimination in 1968, the cost of housing had increased to the point that marginalized communities still struggled to achieve homeownership, according to Miller.

Although racial restrictive covenants were not found everywhere and were fully outlawed over five decades ago, people around the state still found a way to keep communities of color away from their neighborhoods; some real estate agents, for example, wouldn’t show certain properties to non-white buyers, while other residents created an unwelcoming environment, Miller said.

For example, by the 1920s, Chinese immigrants who had been working on Whidbey for decades had all died or left the county after experiencing violence and intimidation at the hands of many of their white neighbors, who would pressure farmers to stop hiring or leasing their property to the Chinese, going as far as setting a Chinese potato pit on fire in 1891, according to information in the Island County Historical Society’s archives.

With slim opportunities for people of color to buy a home, Island County has continued to be predominantly white, though the Navy has been bringing more diversity.

According to a report released by the Economic Development Council in 2022, 78.6% of Island County’s residents are white. In the 1960s, according to UW, that was 97.8% of the population. In 1940, before Naval Air Station Whidbey Island, Island county’s population of 6,098 included only three African Americans and 27 Asian and Indigenous Americans.

Despite some growth, challenges persisted. In an interview with KSER, a radio station based in Snohomish County, the late Carl Gibson recounted his experience as a Black Navy sailor stationed on Whidbey in the 1950s.

Gibson, who would later serve for many years on the Everett City Council before passing away in 2019, recounted being unable to find housing on Whidbey due to the color of his skin. The uniform, he said, made no difference.

“We couldn’t get no closer to Whidbey Island than Everett,” he said, adding that he was only aware of one Black person living farther north, in Mount Vernon.

To this day, discrimination represents a barrier to stable housing, though the full extent of the racist covenants is still unclear, Hughes said. According to Island Roots’ survey, 12% of respondents reported experiencing housing discrimination.

Whether the individuals were people of color, veterans or people with disabilities, addressing these covenants could be an opportunity to address part of an issue that affects everyone, she said.

“Discrimination can happen in many forms, and when we stand for equal access and equal opportunity, everyone benefits from that,” she said.

People of color who lived or whose parents or grandparents lived in Washington before April 1968 may qualify to receive financial support to become homeowners through the Covenant Homeownership Program. For more information, visit wshfc.org/covenant/