While PFAS contamination has become a large concern for both local and national municipalities, Island County’s water experts have been sounding the alarm for another kind of contaminant: seawater intrusion.

As Whidbey Islanders withdraw more from the aquifer, the water may become saltier and saltier. The wells closest to the shore are most susceptible.

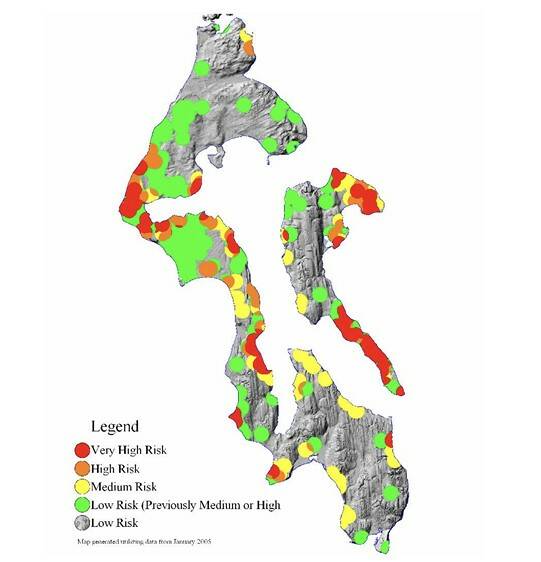

Any well with a screen below sea level could experience seawater intrusion, said Island County Hydrogeologist Chris Kelley. According to the county’s risk map, wells near Ebey’s Landing, West Beach, Libbey Beach, Long Point, Race Lagoon, North Bluff, Greenbank, Useless Bay State Park, Mutiny Bay, Smugglers Cove and Crockett Lake are at a very high risk of saltwater intrusion based on chloride concentration data. Many additional places across the island are at high risk.

Per Island County code, new developments in this area go through much higher scrutiny to protect against seawater intrusion than other areas.

Last year, a group of hydrologists and other stakeholders formed, informally called the Water Cohort, to address this issue and push for legislation to study it.

Seawater intrusion is continually monitored per county code, so Kelley doesn’t see a reason for an additional island-wide study, as the code has been working since it was ratified in 2005 and will be updated as part of the 2025 comprehensive plan amendment.

But to the Water Cohort, time is the greatest concern, said Perry Lovelace, an infrastructure engineering teacher and cohort member. As time goes on — with the threat of sea level rise and predicted influx of people — the problem may get worse and worse.

Some wells along Ebey’s Landing have already turned salty, he said, meaning the chlorine and sodium content in the water has risen to potentially toxic levels. The change is gradual, first affecting the taste until it’s undrinkable.

“Seawater intrusion” is kind of a misnomer, Lovelace said. It’s not an intrusive issue, it’s an overdrawing issue. Seawater doesn’t rush into a well, people draw it in as they deplete the well. As the sea level rises, the aquifer depletes faster, so the problem is going to grow at a faster rate as time goes on. Fixing the problem could mean shutting the well off for a decade.

Ground water becomes saltier as residents continue to pump water, Kelley said.

“It’s not going to be you turn on your water today, it tastes fine. You turn on your water tomorrow and it tastes salty,” he said. “It’s going to be a very gradual shift.”

Chloride is the main contaminant hydrogeologists look at for seawater intrusion, Kelley said, and the maximum contamination level set by the EPA is a taste standard, not a health standard. The water will often taste gross before it causes any serious health harm.

The issue is critical, Lovelace said, because there are really no alternatives to the aquifer.

“Because we’re an island, the only source of freshwater we get is the rain,” he said. “No rivers, no glaciers. It all comes from rainfall, so the hard stop limits of health is how much rain we get.”

Oak Harbor and Naval Air Station Whidbey pipe water in through Deception Pass from a treatment plant on the Skagit River in Mount Vernon. The city of Anacortes, which owns the water right and the plant, sells water to other entities.

A solution that is often suggested is desalinization, Lovelace said, but this really isn’t feasible. It’s expensive in both money and energy, increases fossil fuel emissions and is detrimental to marine life.

County data suggests the island will grow by over 10,000 in the next ten years.

“All those people are thirsty, right?” Lovelace said. “They’re all going to have to have water, and it’s all gonna come from wells.”

There are other warning signs before seawater intrudes, Kelley said. In some wells, he sees elevated fluoride concentrations, which means that they are pumping more freshwater than what the aquifer can supply. This can be remediated by better water practices.

The only truly feasible solution is changing water practices to allow the aquifer more time to recharge, Lovelace said. This means infrastructure designed and built to collect and retain rainwater, such as highway ditches. There are also devices that collect condensation from rooftops.

People can drill a second well to prevent too much pressure on a given area, Kelley said. They can also add a cistern and pump from the well to the top of a cistern to avoid constantly pumping on demand.

“It’s not a death sentence for the well,” he said. “It doesn’t mean that, ‘oh, your chloride went up 10%. You have to shut off the well.’ It just means you have to look at how you’re using the well, and in some cases it can be something as simple as fixing a leaky water line.”

Seawater intrusion can be fixed by a community-wide agreement to put less water on their lawns, he said.

On Whidbey, systems that have experienced seawater intrusion have fixed the problem by drilling a new well and keeping the original well for emergencies. Six years later, the first well’s contaminants had diminished.

The code involving seawater intrusion is addressed in the county’s comprehensive plan, which continues to seek public input for the next year. Through the winter, they will update the policies and goals for the 2025 amendment. Information on individual well data, public system wells and well monitoring can be found on Island County’s Hydrogeology Dashboard.