We must help you. And if we don’t, we’re breaking a federal law.

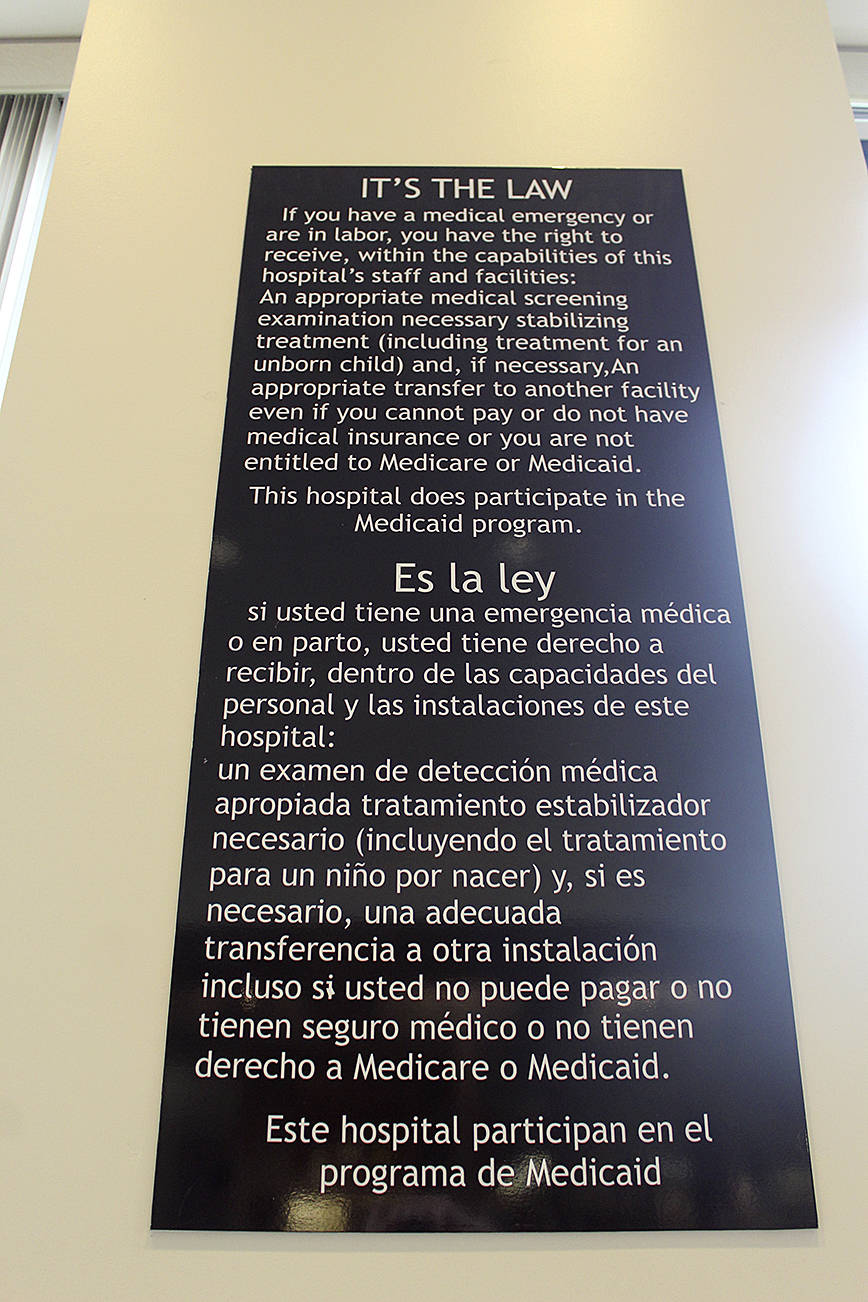

That’s the distilled message in oversized signs recently placed around WhidbeyHealth Medical Center’s front entrance and emergency room.

In white lettering on sheer black background, the signs explain that its emergency department must assist a woman in labor or an individual experiencing a medical emergency regardless of ability to pay.

Additionally, questions about health insurance or finances cannot be asked prior to medical treatment.

Linda Gibson, who oversees the health system’s quality control, explained the federal law called Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act, or EMTALA, at a recent meeting of the Whidbey Island Public Hospital District Board of Commissioners.

The “without delay or ability to pay” law has been around since 1986 and it hasn’t changed, Gibson said. But it’s important that staff and administrators be periodically reminded of its nuances because penalties have recently doubled, she said.

Hospitals can be fined up to $50,000 if found in violation of EMTALA.

The federal law requires signs be posted in a conspicuous location and be able to be read within 20 yards. Previous signs at the hospital were too small and not well-placed, Gibson said in an interview.

Measurements were also recently taken around the perimeter of the emergency room entrance to determine the 250-yard rule of the law, she said.

The law specifies that emergency staff must help a person in medical distress within 250 yards of the emergency department, which is considerably beyond the facility’s parking lot or property lines.

“It’s about two football fields in length,” Gibson said.

A person suffering a heart attack across the street from the medical center is within the 250-yard range. So if a passerby runs in to alert the emergency department, “we have to provide someone from our facility to respond and 911 also needs to be called,” she said.

She cited a 1998 incident in Chicago where a hospital refused to assist a 15-year-old who’d been shot near the hospital but off the facility’s property. Police eventually dragged the boy in but he died.

Ravenswood Hospital Medical Center paid $40,000 to settle the federal complaint. The victim’s family sued and received a $12.5 million settlement, the hospital subsequently closed.

Dr. Nick Perea, chief of staff at WhidbeyHealth, said emergency room caregivers are well-versed on the law and its stipulations about documentation, stabilizing patients and arranging transfers to other facilities.

“We’ve never looked at finances before seeing patients,” he said.

Gibson pointed out that an emergency medical condition includes a mental health crisis. “The topic of mental health is of much discussion in many states,” she said.

An EMTALA compliance plan should be in place to assist individuals experiencing a mental health crisis, Gibson stressed.